Essential Guitar Chord Progressions in Folk Music

Author: Wanda Waterman

Welcome to another instalment of Guitar Chord Progressions by Genre, a series we hope will help make changing chords by ear come naturally to you, easing you through playing your favourite genre as well as many others.

This week we’re bringing you folk music progressions, taking a look at what makes folk progressions different and bringing you a few great songs to play. Keep your Uberchord (click for free download) app handy! (For a bit of background on chord progressions and why it helps to commit them to memory, be sure to check out the previous posts in this series.)

Table of Contents

What is This Thing Called “Folk Music?”

It’s commonly acknowledged that the term “folk music” is used to define two separate musical streams, folk past and folk present:

1) Folk Past: An Ancient Stream of Inspiration

This category comprises those musical traditions, stretching back as far as anyone can remember, created and kept going by poor rural folk who lacked access to higher education. It’s on par with folk art because of its musical simplicity, childlike innocence, authentic emotions, and depiction of humble subjects. In its pure form, it’s nearly always played on acoustic instruments, and most of the songs are written by the venerable A. Nony Mous.

This stream has long been a source of inspiration for “higher,” more sophisticated genres like classical and jazz as well as for rock, reggae, and country music. You’ll often hear old traditional songs reinterpreted by new players again and again even long after everyone has forgotten who wrote the song. Examples include “House of the Rising Sun,” “On Top of Old Smokey,” and “Darlin’ Corey.” There’s something so raw, pure, and human about these songs that they keep coming back to haunt us.

A folksinger in this tradition is not so much a songwriter as a song carrier, interpreting the old songs in his or her own unique style and maybe even adding a verse or two before passing on the song’s essence to the next generation.

Although there’s no typical chord progression in these old songs they often follow the simple I-IV-V-I progression common to most of the western music. But even when this progression is used there are some very interesting variations, for example, the II, III, VI, and VII chords are crammed into the basic progression wherever they can fit.

In folk music from cultures in the Middle East and Africa we often encounter modes, which don’t quite fit the western trio sonata form of (four sets of eight bars) but rather using a short musical phrase, repeating it an undetermined number of times with variations before playing a bridge with a different rhythm and melody. We even find this in the United States in some Native American music and in the blues of Northern Mississippi.

2). Folk Present: Acoustic Introspection, Rousers, and Protest Songs

The second subgenre of folk music is very much inspired by the old traditions and often includes the old songs in its repertoire. Some of the greatest singer-songwriters of the twentieth century started out as folk singers before moving on to musical innovation and writing all their own songs. Even then these songwriters continued to be inspired by tradition and occasionally reinterpreted the old songs.

The newer folksingers tended to go in one of two directions; either they continued being a voice for the voiceless, singing against injustice, like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Buffy Sainte-Marie, or they turned inward, exploring the meanings of their own inner landscapes, like Joni Mitchel, Leonard Cohen, or Neil Young.

But most did both, either because the cruelty of the world drove them inward or because their reflections compelled them to make a compassionate response to suffering.

Folksingers of today carry on this tradition in a myriad of forms, startling in their innovation and in their ability to remain true to the essence of the folk tradition while being relevant to today’s social concerns.

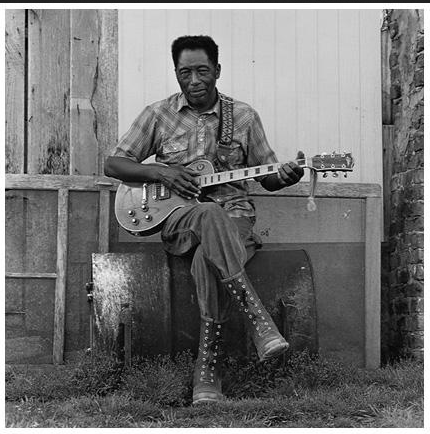

The good news for us is that the guitar is by far the most common instrument in folk music new and old. Wherever you see a folk singer you’re sure to see at least one guitar. Other genres use guitars, but folk music may be the only genre in which you often find a lone singer with a lone guitar.

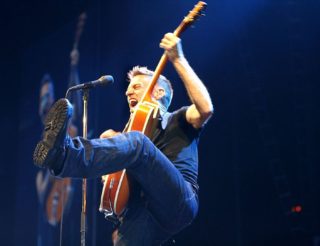

Newer folksingers often find themselves unfairly constrained, especially the guitarists who want to amp things up a bit. True, folk musicians nearly always choose to play acoustic guitars, with a microphone in front at most. But I once worked with a guitarist who warned, “Beware the folk Nazis!” These, he explained, were the people in the audience who insisted that if it had to be plugged in, it wasn’t folk. This may explain why Bob Dylan raised such a uproar when he came on stage sporting an electric guitar. If you do decide to play folk music, stand firm and don’t let the audience dictate your instrumentation. Your guitar, your rules!

A Universal Genre

It can be hard at times to tell which folk songs are old and which new, as some of the most traditional sounding songs have authors who are still alive and whose names we know, and some folk songs that we think of as modern date back hundreds of years.

Unlike most musical genres we’ve been studying, folk music is universal. Rock, blues, jazz, and country music were all spawned in America, but every culture the world over has its own unique folk music traditions. Only classical music can claim this universality, which may be why folk music and classical music can so often be found hand-in-hand. Beethoven used melodies from shepherd songs, Gershwin was inspired by the music of southern African Americans, and both Wagner and Stravinsky based compositions on ancient folklore.

Not only is folk music an international phenomenon, every music genre that exists today has roots in folk. Jazz and rock have roots in blues, which has its roots in American folk songs and African folk dance music as well as the folk musical traditions of the British Isles. Reggae owes its existence not just to American pop genres like rhythm and blues but also to Jamaican mento, a kind of rural folk dance music. (As reggae spread to other countries it also absorbed their folk traditions, as did jazz.) Country music is grounded in old American folk songs and Celtic tunes. And if you investigate the folk idioms of any culture in the world you’ll find that every one of them has the past that recedes back in time indefinitely.

What Sets Folk Guitar Chord Progressions Apart?

For all of the above reasons, there’s no such thing as a standard folk chord progression. It’s even harder to talk about typical chord progressions within folk subgenres, as each subgenre contains varying progressions.

We can, however, say that folk music in general, has certain characteristics that set it apart from other genres. These may come in helpful if you want to rouse your union local to action, send a strong message to the corporate world, or protest a war. Here are just a few things that make folk music different:

- Many songs are in minor keys.

- Songs sung in major keys also use a lot of minor chords.

- Folk is one of the few genres in which it’s permissible to use a VII chord.

- Chord changes are less frequent.

- The progressions use the tonic, or first chord, far more often than in other genres.

- Chords are usually limited to the simple triadic forms, leaving off the extra 6th, 9th, and 13th notes (although V7 chords are common).

Beyond that, the sky’s the limit!

A Few Good Tunes

Many songwriters dig through old folk songs for interesting chord progressions to copy, which is not only perfectly legal (only copying a melody can get you in trouble), the new song usually sounds nothing like the folk song progression it was copied from!

So instead of going into typical folk progressions, we’re going to be talking about the progressions for specific songs in a few folk traditions.

Celtic Music: Siúil a Rún

Celtic music is characterized by intense sentiment. It can be romantic, joyful, or melancholy, but it’s all powerful. This moving love song, about an Irish girl whose lover is leaving for France, is in the key of D-minor. (Note the frequent appearance of the VII chord, which adds a haunting sound.)

I-VII-VI-VII-I

III-VI-VII

I-VII-VI-VII-I

VII-I

Dm C Bb C Dm

I wish I was on yonder hill

F Bb C

‘Tis there I’d sit and cry my fill,

Dm C Bb C Dm

And every tear would turn a mill,

C Dm

Iss guh day thoo avorneen slawn.

Germany: Die Gedanken Sind Frei

This is a great old rouser from Germany. It’s been sung for many years by prisoners, partisans, and revolutionaries, and more recently by the late Leonard Cohen. The title translates as “The mind is free.” This version is in C-major. The progression is very simple, based on the conventional I-IV-V-I progression but repeatedly returning to the I chord for emphasis, creating a proud, confident sound.

I-V-I

I-V-I

V-I-V-I

IV-I-V-I

C G C

I think as I please, and this gives me pleasure.

C G7 C

My conscience decrees– this right I must treasure.

G C G7 C

My thoughts will not cater to duke or dictator.

F C G7 C

No one can deny: Die Gedanken sind frei!

France: Au Clair de La Lune

This old classic is in C here. An interesting musical innovation is that it changes keys for just two bars (the second line of the chorus), which makes for a unique sound.

I-V-IV-V-II-V-IV-V-III

(Key changes to G)

V-I

(Key changes back to C)

I-V-IV-V-I C

C G C G7 C

Au clair de la lune mon ami Pierrot?

G C G7 C

Prête-moi ta plume pour écrire un mot.

G G7

Ma chandelle est morte, je n’ai plus de feu,

C G C G7 C

ouvre-moi ta porte pour l’amour de Dieu.

American: What Wondrous Love is This?

This is a gorgeous old folk hymn from the Appalachian Mountains. The chord progression is simple but haunting, as is the melody. It uses a version of the I-IV-V-I progression but in a minor key. This version is in A-minor.

Progression:

I-V-I

IV-V-I

I-V-I

I-V-I

Am Em Am

What wondrous love is this, oh my soul, oh my soul?

Dm Em Am

What wondrous love is this, oh my soul?

Am

What wondrous love is this

Em Am

That caused the Lord of Bliss

Em Am

To bear the dreadful curse for my soul, for my soul,

Dm Em Am

To bear the dreadful curse for my soul?

Although it’s far from simple-minded (it’s an integral part of many intellectual movements), folk music is relatively easy to play, so when you’re running through your Uberchord training exercises, throw in a few easy folk songs to make it more interesting! There’s many articles that can help you delve deeper into the genre that cover many ways to play these chords, as well as the theory behind the musical structures that make these songs. Browse our blog for more info, or take a look at some of our most recent articles like one about our guitar chord finder app, eb guitar chords, and chords and lyrics to house of the rising sun.

Thank you I was looking for some ideas for a song I have in mind & this helped, great stuff